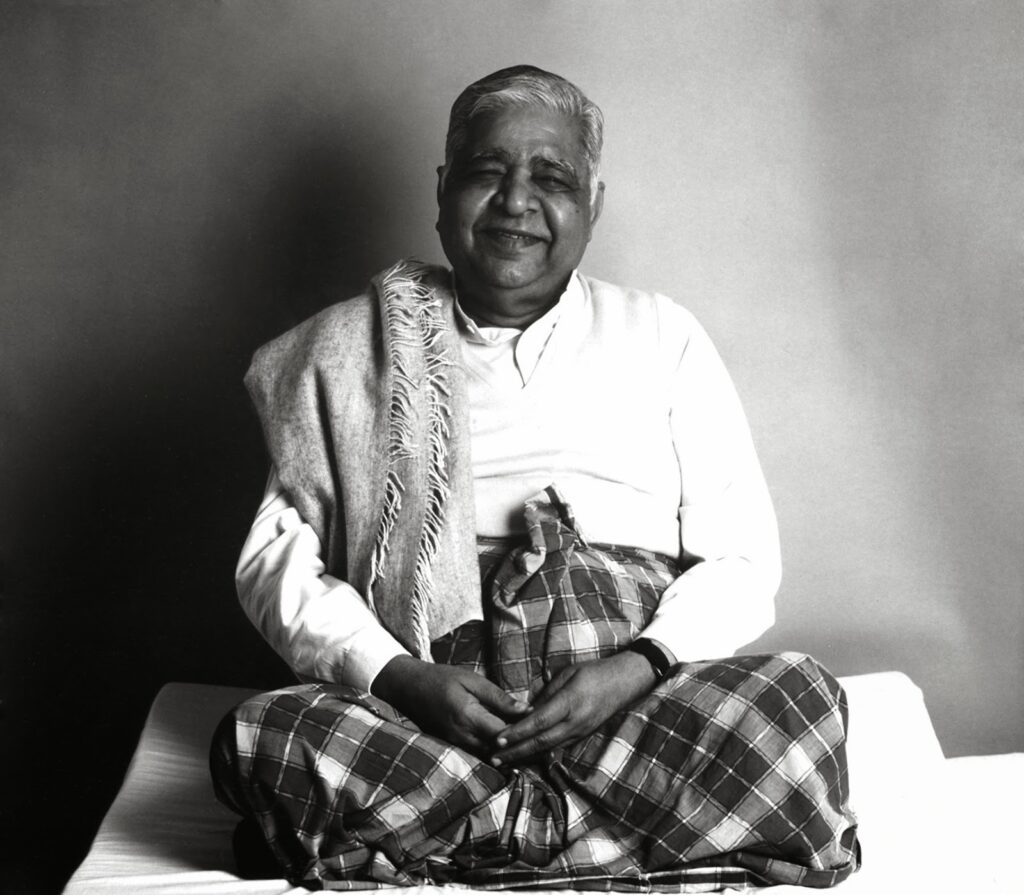

January 30, 1924 – September 29, 2013

May 2011. I awake from extremely vivid dreams, wrap myself in a hoody and head up the hill to the meditation hall.

It’s four AM – my second in ten days of noble silence, my first ever Vipassana meditation retreat. On the first full day, I’d slept through the morning gong and stayed in bed, whilst the other students had dutifully walked to their first (of eight) daily meditation sessions. In blissful semi-consciousness I heard soft footsteps next to my bed, a rustling consultation of paper and a voice – soft and polite, yet clear and unwavering.

“Samuel… Samuel… It’s time to meditate in the hall, Samuel.”

Disgraced, I removed the blanket from my face and grunted “Sorry mate, I must have slept through my alarm.”

My first day of meditation had been refreshing, a real novelty, a real break from it all. This second day is terrible – my legs ache from sitting in a permanent half-lotus position, the gross violation of my sleeping pattern has me in a state of permanent drowsiness, my mind is occupied in dreaming up witty retorts for arguments that took place ten years ago, singling out moments of my past for guilt or regret, and conjuring up sexy images that strut around my inner eye in a pair of six-inch heels.

On the first day, I’d been overcome by an unfamiliar sense of peace and well-being, but today my attitude can be summed up by a single phrase – f**k this.

I feel ashamed of myself for wanting to quit, so I decide to trial the course for one more day. If my itchy feet don’t disappear by the next morning then I’ll grab my rucksack, traipse down the forest trail until I reach the road and then thumb a lift back to San Francisco.

Later that night, the group gather for the Teacher’s Discourse in the meditation hall. The teacher, of course, is Satya Narayan Goenka, the man responsible for exporting the Vipassana meditation technique out of Burma in 1969, first and foremost to cement the practice in it’s original birthplace of India. Now, there are over 170 Vipassana courses located in all corners of the world, so it’s understandable that Mr Goenka can’t join us personally in California, but we have the next best thing – a pre-recorded discourse for each of the ten evenings.

Even from the video screen, the man emanates an air of peace and goodwill. And on that second night, his discourse began something like this:

“So, the second day is over. You are still here… the reality of the practice is setting in… it’s not an easy practice… perhaps it is manifesting itself in all kind of negative thoughts and sensations… and you are thinking – who is this Goenka fellow? What madness is this that he’s trying to do to me? I have to get away from this madman, quickly!”

He smiles, and a collective laugh of recognition sweeps around the entire meditation hall. He understands our discomfort, he lived through it himself, on his first course, and over the next 58 minutes, he spells out the prospective benefits of the art of Dhamma (an art of living in the present moment) with great humour, reason and understanding.

Born in Mandalay to parents of Indian descent, Mr Goenka joined his family’s textile business, quickly becoming a successful, respected businessman. He found, however, that the corporate world left him with severe headaches and mental tension. He attended his first Vipassana course in 1955 under the tutorship of Sayagyi U Ba Khin, a man he would later credit as having the largest influence on his life. The headaches receded, but more importantly, Mr Goenka became a passionate disciple of the practice in its own right. The story goes that U Ba Khin sent Mr Goenka out of Burma to fulfill a prophecy that had been made many centuries ago – that 2,500 years after the life of Buddha, the art of Dhamma would return to it’s homeland, India, and from there spread around the world.

Mr Goenka’s life was spent spreading a message of inclusivity – declaring the practice of meditation a scientific as well as spiritual undertaking, and attempting to move the practice into a secular sphere, away from the religious preserve of ritual for ritual’s sake.

“Religion is religion only when it unites,” Mr Goenka said to applause at the UN World Peace Summit in 2000. “Religion is no religion when it divides. So much has been said for and against religious conversion. I am for conversion, not against it. But conversion not from one organized religion to another organized religion—no. Conversion from misery to happiness. Conversion from bondage to liberation. Conversion from cruelty to compassion. That is the conversion needed today. If I have an agitated mind full of anger, hatred, ill will and animosity, how can I give peace to the world?”

January 2013. I’ve volunteered to work as a kitchen assistant on my second Vipassana course, eager to serve new students, to give them the same learning opportunities that I had. Myself and the other volunteers need no pay, no word of thanks, because we like to believe that, as Mr Goenka might say – ‘ all beings should be happy… all beings be should liberated.’

It’s the second-to-last day of the course, my breakfast shift doesn’t start until 5.30am, and yet I choose to walk to the meditation hall shortly after 4.00. It’s still dark outside. The wind, more ancient even than Dhamma, blows in from the nearby Mojave desert. Inside, most of the students are still in their pyjamas and are wrapped in blankets, but they all face forward together, an eighty-strong block of meditators, filling the silence with a wall of concentration that physically hits me as I step through the door. I take my place on my mat in the front row. Goenka’s chant has already started – the deep voice resonates through the room, acting like a trigger to calm and yet steel my mind. A sensation of strength and clarity runs from the top of my skull down to my lower spine. I observe the sensation, neither grasping at it or allowing it to cause me discomfort. I slip deeper into meditation – the slight chill in the hall causes minute itching sensations in each follicle of each skin cell of my scalp. Like the others in the room, I observe, concentrate, and then allow my attention to drift somewhere else.

Some time passes, I hear Goenka’s chant again – the morning session is coming to a close. I leave the room silently, ready to begin making breakfast for the students. Before I reach the kitchen I find myself alone on a barren stretch of hill that overlooks the valley below. The sun is beginning to rise over the desert – the mountains and sand dunes are lined with an acid green hue – a hue that is smeared upwards through yellow, orange, blue, indigo, midnight blue and black. The stars are still visible in the sky. The wind smells like charred rock. I take a deep breath and realise that this is all I need.

A statement on the Vipassana homepage reads:

“When your own death comes, observe it, at the level of sensations,” Goenka wrote in one of his published works. “Everyone has to observe one’s death: coming, coming, coming, going, going, going, gone! Be happy!”

Shri Satya Narayan Goenka peacefully breathed his last on Sunday evening September 29, at his home in Mumbai, India. He was in his 90th year and had served half his life as a teacher of Vipassana meditation. Through his efforts, hundreds of thousands of people around the world came to learn the path to liberation. Over the years he received many honors but insisted that they were all really for the Dhamma. Following cremation in Mumbai, his ashes were flown to Myanmar and scattered in the Irrawaddy River, reuniting him forever with his beloved homeland.Our deep gratitude to him for the gift of Dhamma. May he be happy, peaceful, liberated!

———————————————

Originally published in September 2013.

Ten or twenty day Vipassana courses are free to attend, and open to all people. Those who wish to pay can make a voluntary contribution at the end of the course. Satisfying vegetarian meals are served three times a day by volunteers who have previously sat a course. There are Dhamma centres in the USA, England, Italy, Sweden, Thailand, India, Argentina, Brazil, Australia, and many other countries of the world.